C2C #1: Game Theory

Types of games

The most simple type of game is the one that we built in the setup section. Cards get flipped over and you either win or lose. Not much skill…and not much fun!

Other games like Bingo, Dreidel, and of course Snakes and Ladders can deceptively seem like you have strategic control of the game, but really this is just the “illusion of agency”, since you’re only, for example, rolling dice to randomize your next move. A disturbing fact:

There are three main classes of games that do have significant strategic agency: perfect information, perfect information with randomness, and imperfect (hidden) information. Perfect information means all game information is visible, while imperfect information meanas there is hidden/private information.

We can also think about games along the axis of fixed or random opponents and adversarial opponents.

(There are also other game classes like sequential vs. simultaneous action games.)

| Game/Opponent | Fixed/Random Opponent | Adversarial Opponent |

|---|---|---|

| No Player Agency/Decisions | Candy Land, War, Dreidel, Bingo, Snakes and Ladders | Blackjack dealer |

| Perfect Info | Puzzles, Rubik’s Cube | Tictactoe, Checkers, Chess, Arimaa, Go, Connect Four |

| Perfect Info with Randomness | Monopoly, Risk | Backgammon |

| Imperfect Info | Wordle, Blackjack | Poker, Rock Paper Scissors, Figgie, StarCraft |

Perfect information games

Perfect information games like Chess and Go are complex and have been the focus of recent AI research (along with poker). Solving these games can theoretically be done using backward induction, which means starting from possible end positions and working backwards.

Imperfect information games

Here we want to primarily focus on the bottom right of this chart: imperfect information games with an adversarial opponent.

These games cannot be solved in the same way as perfect information games because we don’t know always what true state of the game we are in because of the hidden information (we’ll look at this more in Game Trees).

Imperfect information games are representative of real world situations where information is usually incomplete, e.g. job interviews, investments, dating, and negotiations.

Winning games

The goal of a game is to maximize the utility, which is usually a score or money or some kind of value.

There are two fundamental strategies:

Exploiting opponent weaknesses: Capitalize on specific flaws or tendencies of opponents, while putting yourself at risk if the opponent adapts well.

Being unexploitable: Playing a balanced, theoretically sound strategy, also known as game theory optimal. This does not maximize against weaker opponents, but rather aims to minimize losses against any possible opponent.

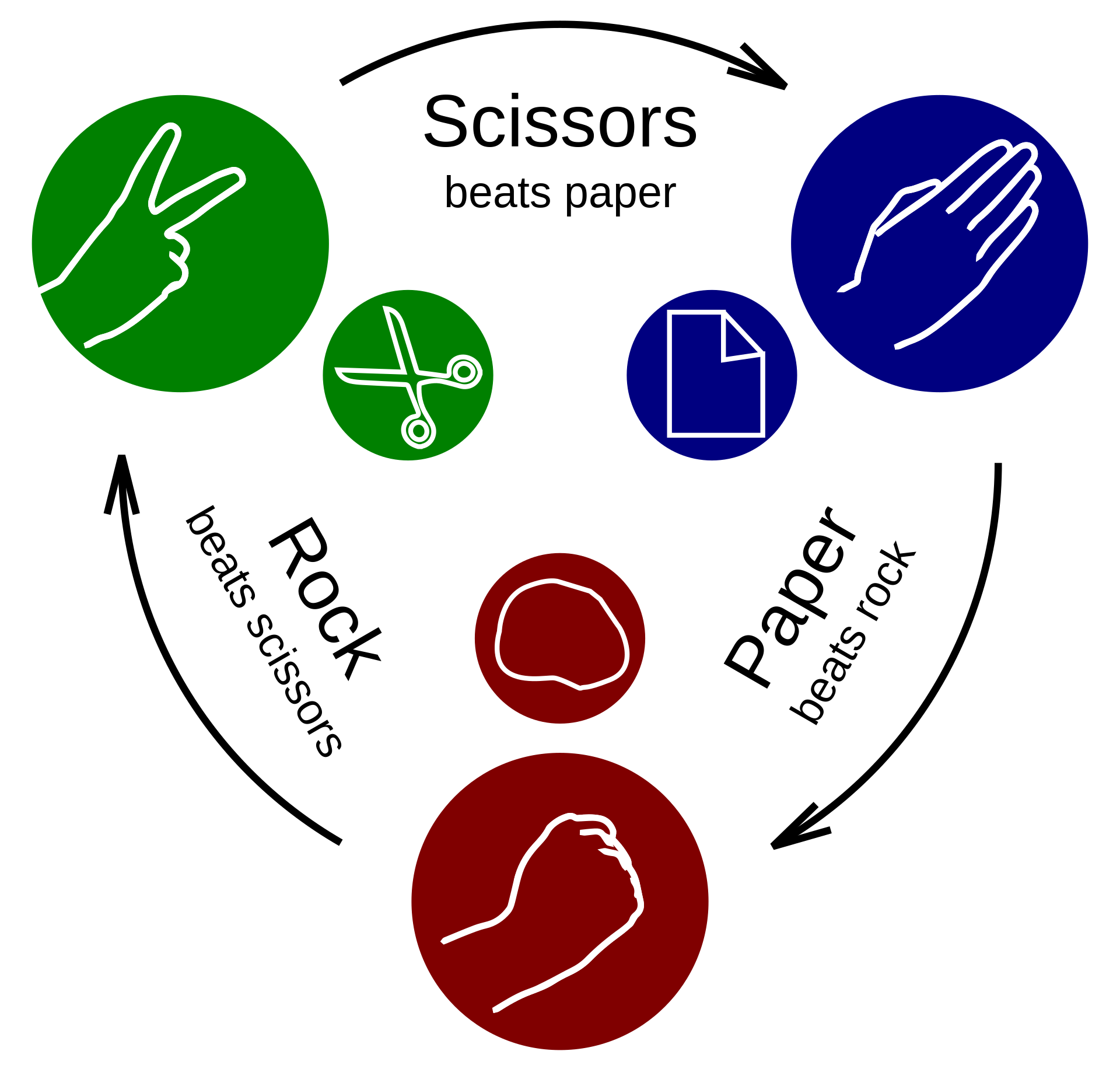

Rock Paper Scissors

- Rock defeats scissors, scissors defeats paper, and paper defeats rock

- You get +1 point for a win, -1 for a loss, and 0 for ties

This simple game was the subject of a DeepMind paper in 2023, where they wrote:

In sequential decision-making, agent evaluation has largely been restricted to few interactions against experts, with the aim to reach some desired level of performance (e.g. beating a human professional player). We propose a benchmark for multiagent learning based on repeated play of the simple game Rock, Paper, Scissors.

Let’s dig in to why RPS is a more interesting game than it might seem.

Payoff matrix

The core features of a game are its players, the actions of each player, and the payoffs. We can show this for RPS in the below payoff matrix, also known as normal-form.

| Player 1/2 | Rock | Paper | Scissors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rock | (0, 0) | (-1, 1) | (1, -1) |

| Paper | (1, -1) | (0, 0) | (-1, 1) |

| Scissors | (-1, 1) | (1, -1) | (0, 0) |

The payoffs for Player 1 are on the left and for Player 2 on the right in each payoff outcome of the game. For example, the bottom left payoff is when Player 1 plays Scissors and Player 2 plays Rock, resulting in -1 for P1 and +1 for P2.

A strategy says which actions you would take for every state of the game.

Expected value

Expected value in a game represents the average outcome of a strategy if it were repeated many times. It’s calculated by multiplying each possible outcome by its probability of occurrence and then summing these products.

Suppose that Player 1 plays the strategy:

\begin{cases} r = 0.5 \\ p = 0.25 \\ s = 0.25 \end{cases}

and Player 2 plays the strategy:

\begin{cases} r = 0.1 \\ p = 0.3 \\ s = 0.6 \end{cases}

Let’s add these to the matrix:

| Player 1/2 | Rock (r_2=0.1) | Paper (p_2=0.3) | Scissors (s_2=0.6) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rock (r_1=0.5) | (0, 0) | (-1, 1) | (1, -1) |

| Paper (p_1=0.25) | (1, -1) | (0, 0) | (-1, 1) |

| Scissors (s_1=0.25) | (-1, 1) | (1, -1) | (0, 0) |

To simplify, let’s just write the payoffs for Player 1 since payoffs for Player 2 will simply be the opposite:

| Player 1/2 | Rock (r_2=0.1) | Paper (p_2=0.3) | Scissors (s_2=0.6) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rock (r_1=0.5) | 0 | -1 | 1 |

| Paper (p_1=0.25) | 1 | 0 | -1 |

| Scissors (s_1=0.25) | -1 | 1 | 0 |

Now we can multiply the player action strategies together to get a percentage occurrence for each payoff in the matrix:

| Player 1/2 | Rock (r_2=0.1) | Paper (p_2=0.3) | Scissors (s_2=0.6) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rock (r_1=0.5) | Val: 0 Pr: 0.5(0.1) = 0.05 |

Val: -1 Pr: 0.5(0.3) = 0.15 |

Val: 1 Pr: 0.5(0.6) = 0.3 |

| Paper (p_1=0.25) | Val: 1 Pr: 0.25(0.1) = 0.025 |

Val: 0 Pr: 0.25(0.3) = 0.075 |

Val: -1 Pr: 0.25(0.6) = .15 |

| Scissors (s_1=0.25) | Val: -1 Pr: 0.25(0.1) = 0.025 |

Val: 1 Pr: 0.25(0.3) = 0.075 |

Val: 0 Pr: 0.25(0.6) = .15 |

Note that the total probabilities sum to 1 and each row and column sums to the probability of playing that row or column.

We can work out the expected value of the game to Player 1 (summing all payoffs multiplied by probabilities from top left to bottom right):

\mathbb{E}[P_1] = 0(0.05) + -1(0.15) + 1(0.3) + 1(0.025) + 0(0.075) + -1(0.15) + -1(0.025) + 1(0.075) + 0(0.15) = 0.075

Therefore P1 is expected to gain 0.075 per game given these strategies. Since payoffs are reversed for P2, P2’s expectation is -0.075 per game.

Zero-sum

We see in the matrix that every payoff is zero-sum, i.e. the sum of the payoffs to both players is 0. This means the game is one of pure competition. Any amount P1 wins is from P2 and vice versa.

Nash equilibrium

A Nash equilibrium means that no player can improve their expected payoff by unilaterally changing their strategy. That is, changing one’s strategy can only result in the same or worse payoff (assuming the other player does not change).

In RPS, the Nash equilibrium strategy is to play each action r = p = s = 1/3 of the time. I.e., to play totally randomly.

Played a combination of strategies is called a mixed strategy, as opposed to a pure strategy, which would select only one action. Mixed strategies are useful in games of imperfect information because it’s valuable to not be predictable and to conceal your private information. In perfect information games, the theoretically optimal play would not contain any mixing (i.e., if you could calculate all possible moves to the end of the game).

The equilibrium RPS strategy is worked out below:

Playing this strategy means that whatever your opponent does, you will breakeven! For example, think about an opponent that always plays Rock.

\begin{equation} \begin{split} \mathbb{E}(\text{Equilibrium vs. Rock}) &= 0(r) + 1(p) + -1(s) \\ &= 0(1/3) + 1(1/3) + -1(1/3) \\ &= 0 \end{split} \end{equation}

How about the case of the opponent playing 60% Rock, 20% Paper, 20% Scissors?

\begin{equation} \begin{split} \mathbb{E}(\text{Equilibrium vs. 622}) &= 0.6(\text{Equilibrium vs. Rock}) \\ &\quad{}+ 0.2(\text{Equilibrium vs. Paper}) \\ &\quad{}+ 0.2(\text{Equilibrium vs. Scissors}) \\ &= 0.6(0) + 0.2(0) + 0.2(0) \\ &= 0 \end{split} \end{equation}

The random equilibrium strategy will result in 0 against any pure strategy and any combination of strategies including 622 and the opponent playing the random strategy.

Exploiting vs. Nash

The equilibrium strategy vs. a pure Rock opponent is a useful illustration of the limitations of playing at equilibrium. The Rock opponent is playing the worst possible strategy, yet equilibrium is still breaking even!

What’s the best that we could do against Rock only? We could play purely paper. The payoffs are written for playing Paper and the probabilities indicate the opponent playing only Rock.

\begin{equation} \begin{split} \mathbb{E}(\text{Paper vs. Rock}) &= 1(r) + 0(p) + -1(s) \\ &= 1(1) + 0(0) + -1(0) \\ &= 1 \end{split} \end{equation}

We’d win 1 each game playing Paper vs. Rock.

How about against the opponent playing 60% Rock, 20% Paper, 20% Scissors? Here we can see that because they are overplaying Rock, our best strategy is again to always play Paper. We write the payoffs for playing Paper and the probabilities according to the 622 strategy.

\begin{equation} \begin{split} \mathbb{E}(\text{Paper vs. 622}) &= 1(r) + 0(p) + -1(s) \\ &= 1(0.6) + 0(0.2) + -1(0.2) \\ &= 0.6 + 0 - 0.2 \\ &= 0.4 \end{split} \end{equation}

Playing Paper vs. 622 results in an expected win of 0.4 per game.

Soccer Kicker vs. Goalie

Consider the Soccer Penalty Kick game where a Kicker is trying to score a goal and the Goalie is trying to block it.

| Kicker/Goalie | Lean Left | Lean Right |

|---|---|---|

| Kick Left | (0, 0) | (2, -2) |

| Kick Right | (1, -1) | (0, 0) |

The game setup is zero-sum. If Kicker and Goalie both go in one direction, then it’s assumed that the goal will miss and both get 0 payoffs. If the Kicker plays Kick Right when the Goalie plays Lean Left, then the Kicker is favored and gets a payoff of +1. If the Kicker plays Kick Left when the Goalie plays Lean Right, then the kicker is even more favored, because it’s easier to kick left than right, and gets +2.

Nash equilibrium?

Which of these, if any, is a Nash equilibrium? You can check by seeing if either player would benefit by changing their action.

| Kicker | Goalie | Equilibrium or Change? |

|---|---|---|

| Left | Left | |

| Left | Right | |

| Right | Left | |

| Right | Right |

Assume that they both play randomly – Left 50% and Right 50% – what is the expected value of the game?

Probabilistic interpretations

Note that, for example, the Kicker playing 50% Left and 50% Right could be interpreted as a single player having these probabilities or a field of players averaging to these probabilities. So out of 100 players, this could mean:

- 100 players playing 50% Left and 50% Right

- 50 players playing 100% Left and 50 players playing 100% Right

- 50 players playing 75% Left/25% Right and 50 players playing 25% Left/75% right

Finding equilibrium

When the Goalie plays left with probability p and right with probability 1-p, we can find the expected value of the Kicker actions.

| Kicker/Goalie | Lean Left (p) | Lean Right (1-p) |

|---|---|---|

| Kick Left | (0, 0) | (2, -2) |

| Kick Right | (1, -1) | (0, 0) |

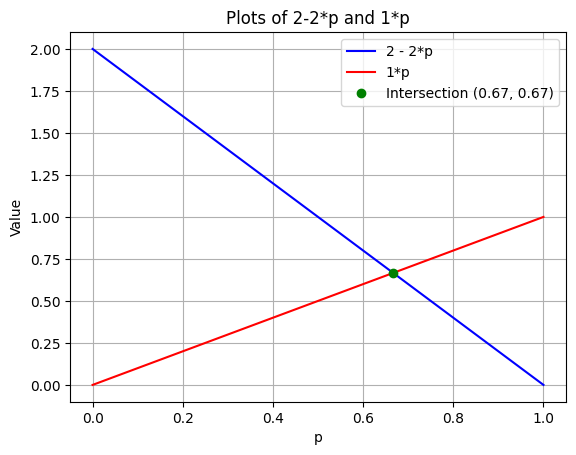

\mathbb{E}[K(L)] = p(0) + (1-p)(2) = 2 - 2p

\mathbb{E}[K(R)] = p(1) + (1-p)(0) = p

The Kicker is going to play the best response to the Goalie’s strategy. The Goalie wants to make the Kicker indifferent to Kick Left and Kick Right because if the Kicker was not going to be indifferent, then he would prefer one of the actions, meaning that action would be superior to the other. When you make your opponent indifferent, then you don’t give them any best play.

Therefore the Kicker will play a mixed strategy in response that will result in a Nash equilibrium where neither player benefits from unilaterally changing strategies. (Note that indifferent does not mean 50% each, but means the expected value is the same for each.)

By setting the values equal, we get 2 - 2p = p \Rightarrow p = \frac{2}{3} as shown in the plot.

This means that 1-p = 1 - \frac{2}{3} = \frac{1}{3}.

Therefore the Goalie should play Lean Left (p) \frac{2}{3} and Lean Right (1-p) \frac{1}{3}.

The value for the Kicker is \frac{2}{3}, or (0.67), for both actions, regardless of the Kicker’s mixing strategy.

Note that the Kicker is worse off now (0.67 now compared to 0.75) than when both players played 50% each action. Why?

If the Kicker plays Kick Left with probability q and Kick Right with probability 1-q, then the Goalie’s values are:

\mathbb{E}[G(L)] = 0(q) - 1(1-q) = -1 + q

\mathbb{E}[G(R)] = -2q + 0(1-q) = -2q

Setting equal,

\begin{equation} \begin{split} -1 + q &= -2q \\ -1 &= -3q \\ \frac{1}{3} &= q \end{split} \end{equation}

Therefore the Kicker should play Kick Left (q) \frac{1}{3} and Kick Right (1-q) \frac{2}{3}, giving a value of -\frac{2}{3} to the Goalie.

We can see this from the game table:

| Kicker/Goalie | Lean Left (\frac{2}{3}) | Lean Right (\frac{1}{3}) |

|---|---|---|

| Kick Left (\frac{1}{3}) | Val: (0, 0) Pr: \frac{2}{9} |

Val: (2, -2) Pr: \frac{1}{9} |

| Kick Right (\frac{2}{3}) | Val: (1, -1) Pr: \frac{4}{9} |

Val: (0, 0) Pr: \frac{2}{9} |

Therefore the expected payoffs in this game are:

\mathbb{E}[K] = \frac{2}{9}(0) + \frac{1}{9}(2) + \frac{4}{9}(1) + \frac{2}{9}(0) = \frac{6}{9} = 0.67 for the Kicker and -0.67 for the Goalie.

Switching out of equilibrium

In equilibrium, both players are playing a best response against each other, giving no incentive to deviate.

Therefore no player can unilaterally improve by changing their strategy. What if the Kicker switches to always Kick Left?

| Kicker/Goalie | Lean Left (\frac{2}{3}) | Lean Right (\frac{1}{3}) |

|---|---|---|

| Kick Left (1) | Val: (0, 0) Pr: \frac{2}{3} |

Val: (2, -2) Pr: \frac{1}{3} |

| Kick Right (0) | Val: (1, -1) Pr: 0 |

Val: (0, 0) Pr: 0 |

Now the Kicker’s payoff is still \frac{2}{3}(0) + \frac{1}{3}(2) = 0.67.

When a player makes their opponent indifferent, this means that any action the opponent takes (within the set of equilibrium actions) will result in the same payoff! But now they are no longer in equilibrium.

So if you know your opponent is playing the equilibrium strategy, then you can actually do whatever you want with no penalty with the mixing actions. Sort of.

The risk is that the opponent can now deviate from equilibrium and take advantage of your new strategy. For example, if the Goalie caught on and moved to always Lean Left, then the value is reduced to 0 for both players. Though if the Kicker then caught on and moved to always Kick Right, then the value goes up to 1 for the Kicker and -1 for the Goalie. Perhaps after a few cycles like this, the players would go back to equilibrium.

To summarize, you can only be penalized for not playing the equilibrium mixing strategy if your opponent plays a non-equilibrium strategy that exploits your strategy. You can only profit more than the equilibrium strategy if your opponent either plays off equilibrium and you do as well or if you play equilibrium and they play some action that is not part of the equilibrium strategy (also known as the support, or the set of pure strategies that are played with non-zero probability under the mixed strategy, which is not possible in this game since both possible actions are played at equilibrium).

Clairvoyance Poker

Back to poker. We previously built Face-up 3-card Poker where each player was dealt a card from the deck of {0, 1, 2} and the high card won.

Now we’re going to make a small change to the game, while keeping the same deck.

Player 1 will always be dealt card 1.

Player 2 will be dealt randomly from {0, 2}.

P1 knows P2 has either card 0 or 2, but not which. P2 knows that P1 has card 1.

This is representative of a real poker scenario where P1 has a mid-strength hand that can beat bluffs, but loses to value bets by strong hands. P2 has either a bluff (weak hand) or a strong hand.

Let’s modify the code to update the deal:

Equity and Variance

Equity is defined as the percentage of the pot expected to win given the cards, assuming no additional betting. We see that in the original case where players were randomly dealt cards and in this case, both players have 50% equity before the cards are dealt. After the cards are dealt, the higher card has 100% equity.

In real poker games like Texas Hold’em, equity is more interesting because there are additional community cards that mean that even if one hand starts off as stronger, it won’t necessarily win. Below we have a special poker hand where the equities are shown as 53% and 47% and the hand currently losing actually has higher equity!

Variance measures the spread of the score differences. Higher variance means more volatility in the outcomes.

We can run a sample of games and get an empirical sample for:

- Equity:

- Variance

- Winrate:

Standard Error: This measures the precision of our sample mean as an estimate of the population mean. Confidence Interval: This gives us a range where we expect the true population mean to lie with 95% confidence.

Betting Rules and Sequences

Let’s make this a real strategic poker game with betting. This game, Clairvoyance Poker, was first shown in The Mathematics of Poker (Bill Chen, Jared Ankenman) and then also in the excellent Play Optimal Poker (Andrew Brokos).

Both players ante 1 chip, so the starting pot is 2

Each player has 1 remaining chip to use for betting

Player 1 acts first and can either Bet 1 or Check (Pass)

Play continues until one of these betting sequences happens, which ends the hand:

Check Check: Hands go to showdown and player with highest card wins 1 (the ante)

Bet Call: Hands go to showdown and player with highest card wins 2 (the ante + bet)

Bet Fold: Player who bets wins 1 (the ante)

Here is a list of all possible betting sequences:

| P1 | P2 | P1 | Winner |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bet | Fold | P1 (+1) | |

| Bet | Call | Higher Card (+2) | |

| Check | Check | Higher Card (+1) | |

| Check | Bet | Fold | P2 (+1) |

| Check | Bet | Call | Higher Card (+2) |

Starting Strategies

There are six possible states of the game, two for P1 and four for P2. Let’s hard-code some initial strategies for both players:

- P1[1, Starting]: Randomly Bet/Check

- P2[0, After Bet]: Fold

- P2[2, After Bet]: Call

- P2[0, After Check]: Randomly Bet/Check

- P2[2, After Check]: Bet

- P1[1, After Check and Bet]: Randomly Bet/Check

This strategy randomizes uncertain decisions and takes clearly smart decisions when possible. What does that mean?

- P2[0, After Bet]: Fold

- This is the worst card and can’t win

- P2[2, After Bet]: Call

- This is the best hand and guarantees a win

- P2[2, After Check]: Bet

- This is the best card and betting can only possibly win additional chips

Let’s put the strategies into our code and see how each strategy is doing. There are 9 total state-action pairs bolded below:

- P1[1, Starting]: Randomly Bet/Check

- P1[1, Starting]: Bet

- P1[1, Starting]: Check

- P2[0, After Bet]: Fold

- P2[2, After Bet]: Call

- P2[0, After Check]: Randomly Bet/Check

- P2[0, After Check]: Bet

- P2[0, After Check]: Check

- P2[2, After Check]: Bet

- P1[1, After Check and Bet]: Randomly Call/Fold

- P1[1, After Check and Bet]: Call

- P1[1, After Check and Bet]: Fold

For now, we’ll do this in a simple, but not-so-elegant way.

—> Logic for taking these actions

—> Logic for keeping track of frequency of each situation/action and results for each situation/action (and still output stuff from before)

Dominated Strategy

Note that P1 betting is strictly worse and why –> show math

–> Update logic to always check

- P1[1, Starting]: Check

- P2[0, After Bet]: Fold

- P2[2, After Bet]: Call

- P2[0, After Check]: Randomly Bet/Check

- P2[0, After Check]: Bet

- P2[0, After Check]: Check

- P2[2, After Check]: Bet

- P1[1, After Check and Bet]: Randomly Call/Fold

- P1[1, After Check and Bet]: Call

- P1[1, After Check and Bet]: Fold

Your Strategies

—> Try strat for P1 then for P2 See results

- P1[1, Starting]: Check

- P2[0, After Bet]: Fold

- P2[2, After Bet]: Call

- P2[0, After Check]: ??

- P2[2, After Check]: Bet

- P1[1, After Check and Bet]: ??

Indifference in Poker

There are two strategies for which we can find an equilibrium:

- P2[0, After Check]: ??

- P1[1, After Check and Bet]: ??

Let’s start by looking at the EVs for P2’s action with card 0 facing a Check.

\mathbb{E}[P2](0,Check) = 0 \mathbb{E}[P2](0,Bet) = 2(\Pr(\text{P1 Fold})) + -1(\Pr(\text{P1 Call}))

These should be equal in order for P2 to be indifferent. Let \Pr(\text{P1 Call}) = p and \Pr(\text{P1 Fold}) = 1-p.

Note that we set the Check action to have an EV of 0 because we are counting any chips already in the pot as already used.

We solve for the P1 strategy that makes P2 indifferent.

\begin{equation} \begin{split} 0 &= 2(1-p) - p \\ 0 &= 2 - 2p - p \\ 3p &= 2 \\ p &= 2/3 \end{split} \end{equation}

Therefore P1 should play $p =

Now let’s look at the EVs for P1’s action with card 1 facing a Bet after Checking.

\mathbb{E}[P1](1,Fold) = 0 \mathbb{E}[P2](1,Call) = 3(\Pr(\text{P2 Card 0 and Bets})) + -1(\Pr(\text{P2 Card 2 and Bets}))

We know that \Pr\text{P2 Card 2 and Bets} = \frac{1}{2}(1) since P2 has the card half the time and bets always with the card.

Let b represent how often P2 bluffs with card 0.

\Pr(\text{P2 Card 0 and Bets}) = (1/2)(b)

Now to equate the two equations above, we have:

0 = 3(1/2)(b) - 1/2 b = 1/3

Therefore P2 will bet 1/3 of the time with card 0 facing a Check, i.e. P2 will bluff 1/3 of the time with the Q.

Note that the indifference equation also accounts for how often P2 is betting with card 2 and we are really thinking about an overall strategy for playing the range of cards {0, 2}.

One additional step is that we can compute the overall ratio of bluffs vs. value bets that P1 is facing.

P2 has card 0 and 2 each \frac{1}{2} of the time.

P2 is betting card 0 \frac{1}{3} of the time (bluffing).

P2 is betting card 2 always (value betting).

Therefore for every 3 times with card 0 you will bet once and for every 3 times with card 2 you will bet 3 times. Out of the 4 bets, 1 of them is a bluff.

\Pr(\text{P2 Bluff after P1 Check}) = \frac{1}{4}

Overall we have this strategy for P2:

- 2/6: Give up (check) with card 0

- 1/6: Bluff with card 0

- 3/6: Value bet with card 2

If P2 bet \frac{2}{3} instead of \frac{1}{3} with card 0 after P1 checks and P1 is playing an equilibrium strategy, how would P2’s expected value change?

Equity vs. Expected Value

can tell opponent strategy to bet 1/3 0s but can’t stop call more catches more bluffs, but pays off more value bets

Sometimes have to bluff with bad cards because EV higher than if you always folded with bad cards.

Add uncertainty the opponent has to think about in counter-strategy If always folded bad cards, opponent knows you keep playing with good #

exploits

bet all good, check all bad opponent can always fold Then switch to always betting Then switch to awlasy calling Then move to betting strong, checking weak

bluffing combined with value betting is the profitable thing. players who fold too often lose to bluffs, call too often lose value to value bets. betting to bluff and call ratios adepend on pot size

Bonus: Bet Sizing

pot sizing affects strategy pot large etc. –> Add pot size stuff pot odds

1 - bet/(bet+pot) larger bet means call less, let them get away with bluffs the bigger they bet

bluff to value ratio bet/(bet+pot) bluffing frequency goes up as bet size gets larger relative to pot